Craft talk: Point of View

How should your story unfold?

Certain genres lend themselves toward particular points of view; for example, chick lit or cozy mysteries are often told in first person to bring the reader in close for a shared experience. Who should tell your story? And how? How many different people need to share themselves with your reader and why?

Consider your story:

- Will your character simply tell/share his or her story? Probably third person, past tense may be best.

- Do you want your readers to experience every bit of nuance a characters goes through? A closer perspective may be best, if not first person, then deep/close third.

- Is your story something best told to your reader or another character in the manuscript (a story within a story)? If you plan to address the audience, you can consider second person, which is a rare technique. Often best in children’s books and nonfiction, monologues or epistolary manuscripts.

- Is your story’s setting acting like a character, driving action and reaction? Perhaps multiple viewpoints to show character/theme arc will serve your story the best.

Which character(s) should tell the story?

Ask yourself: Whose story is it? Which character(s) have the most to lose or gain? What type of story is it? Who’s got all the secrets or lies? Women’s fiction should generally be single point of view. Often romantic stories are told from both heroine and hero’s sides. Steven James lets his bad guy have a monologue throughout his thrillers. Is the character aware of the ulterior motives of others? How can you make that happen if the story has only one perspective? Is the POV character the only holder of a secret? How many others must the character affect? How likeable, personable, intriguing, believable, is he or she?

Are multiple viewpoints better than single character point of view?

Not necessarily, but sometimes. Maybe. At the risk of confusing your reader, ask yourself how information is best conveyed to your reader. What must the reader absolutely have to know to get to the conclusion/denouement? Are you sure (x) is the only one who can give your reader what he or she needs to follow along or experience the story? Is this speaker reliable? Are all of your speaking characters driving your story toward the natural wrap? Who survives? Who doesn’t? Allowing your readers to invest in temporary, throwaway people cheats and wastes space. Unless you have a sinister need, killing off your single POV main character (permanently) hurts your chance of a successful series. Think spin-off or series. Sometimes they work, other times, not so well. An obvious set-up for such a spin-off is necessary for success; at least hint, or certainly provide very strong sub-characters and sub-plots with natural beginnings, middles, and ends that can develop into their own stories.

Changing tenses with alternating voices or scenarios

Letting your characters alternate past and present by using present tense can be effective but is tricky to pull off. Any time you, the author, intrude, or make a mistake, you pull your reader out of the story, the experience. The reader may not even know why they dropped out of warp, but will know that something happened and it is not good. Using different font styles, such as italics, to show internal monolog (present tense), or some other type of change in time, can be effective if used organically so the reader can follow the rhythm and pace. The technique can also be supremely annoying if it serves no purpose. If using a technique such as deep or close third POV, using italics to set off internal monolog is unnecessary, as the reader knows we’re not changing perspective. Changing tense from past to present for internal monolog does not make a difference in intensity or timeline.

Alternating first and third with other points of view

If done organically, it can work and shouldn’t be obvious to the reader.

Points of View vocabulary:

First – “I” am telling my story. You only see what I see, and I cannot read minds or know who sticks out a tongue when my back is turned unless someone else in the room tells me. I cannot overhear conversations in another part of the house, or see through walls unless I have superpowers. It’s limiting, but freeing. Be your character. Share and move forward based only what she sees/knows/experiences.

Second – “You” are going to get a kick out of my story, get it? Your characters address others/audience as “you,” bringing them into the narrative outside of dialog/quoted conversation. Think Shakespeare’s asides.

Third – he said, said she. She and He or It conveys the narrative, one head/one voice at a time. The readers has a good grasp of character development; perspective and/or internal narrative is from one character per scene/chapter.

Other:

Limited – refers to the concept that the reader is aware of only what the character can see/hear/know/conclude or deduce from events happening around him or her

Deep/Close Third – a fairly recent concept in that a character tells a story in third person, but without the use of “padding” such as dialog tags, explanatory phrases such as he felt or she saw, or simile phrases such as she felt, it was like/as if. Deep or Close Third POV brings the reader in tight, almost like first person, to experience and participate in emotions or responses vs. “telling” the reader the result or outcome of the stimuli.

Plural First Person – using “we” in situations where the narration is by a group which may have one or more speakers telling the story through the eyes of the group, such as a group of emigrants or POWs.

Alternating – using more than one character to tell the story. Limit character’s perceptions and narrative/dialog to a scene. Make sure it’s vital that such information to drive the story comes only from this character for a very specific reason. It’s like telling two (or more) sides of a story. But ask, is it necessary? Can the information come another way? Is the information itself necessary? What if it’s not there? What will happen?

Omniscient – A narrator of your story knows what’s going on for everyone—this someone knows what everyone is thinking, what they’ve done, and what they will do/say, and how it will turn out. This technique best employs am outside voice, such as the Stage Manager in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, Death, the undead or ghost, an archangel, or something else unnatural such as a disease, landmark, era. The omniscient speaker knows but does not influence events/actions. See attached article on Omniscient POV.

Please note: Head-Hopping is NOT Omniscient Voice/POV. Head-hopping happens when the reader cannot tell who is narrating because you, the author, have not allowed your characters the dignity of speaking for themselves. You interrupt your protagonist with intruding perspectives as if everyone is a mind-reader but no one will listen to each other’s thoughts. BORING! Why bother having a main character when you can be everybody?

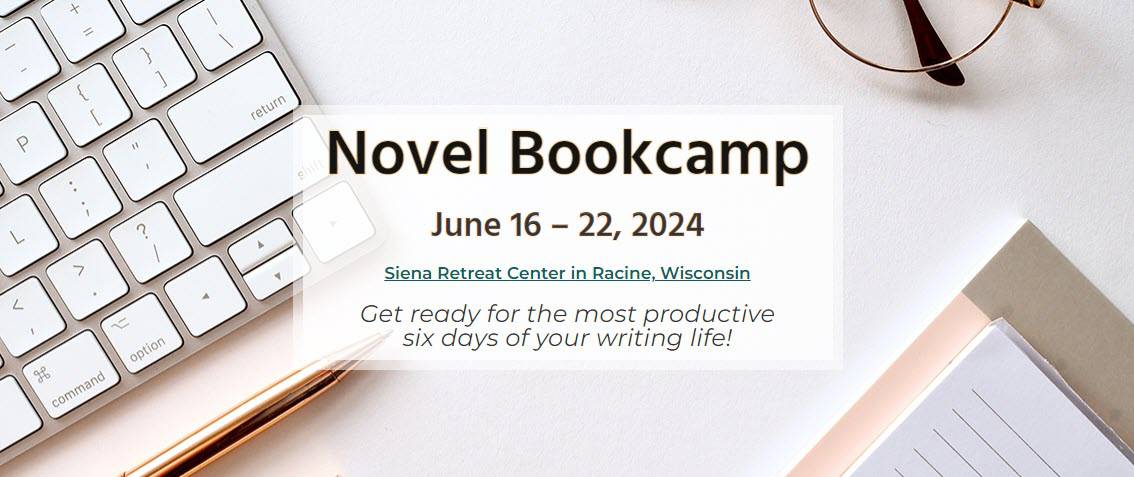

Come to Bookcamp and learn how to optimize your story.