What a Character! Writing Tips

Good characters can make or break a story. Readers want to identify with a character, no matter if it’s the good guy or the bad guy, they want to root and boo, suffer with and experience what your character goes through on their journey in your book. Readers want to have a good time, maybe learn something, and ponder over the dilemma you create. When learning to develop good characters, here are a few writing tips:

Good characters can make or break a story. Readers want to identify with a character, no matter if it’s the good guy or the bad guy, they want to root and boo, suffer with and experience what your character goes through on their journey in your book. Readers want to have a good time, maybe learn something, and ponder over the dilemma you create. When learning to develop good characters, here are a few writing tips:

Character Vocabulary

Protagonist (Hero, Heroine) – the main character, no matter the personality; often answers the questions “whose story is this?” and “who has the most to lose?”

Antagonist (Villain) – the character/dilemma/group that opposes the protagonist and creates the conflict(s); often answers the questions “who/what keeps the goal from being achieved?” and “who has the most to gain?”

Antihero – the character after the mc, combines both good and evil, acts the opposite of a traditional hero, clumsy, nerdy, etc. Not necessarily all negative like they have been lately in shows, etc. They have great need or great need to right a wrong or stay true to the nature that compels them

Sidekick – often companion of the main characters who support the mc, or may drive subplots which support the main storyline

What makes a memorable character?

Every characters has a need, whether it’s obvious, on the sleeve, underlying—everyone acts on that need. The more people affected, the higher the stakes; the more universal the story & setting, the greater the audience. When you move your story beyond something about so and so will die if x doesn’t happen, or the mc will never be happy if y doesn’t happen (who cares), to saving the town/planet/agriculture/atmosphere, prevent genocide, etc., the wider the appeal to a greater audience. These needs can be obvious, or subtle/future events hinted at, or controversial.

Consider:

Main/universal needs (humans need to breathe and eat)

Higher stakes needs that go beyond personal (community development, species survival)

Needs under extenuating circumstances (protection, from shelter/clothing to

communication, transportation, means of trade)

Needs that satisfy temporary wants or permanent wants (possessions, authority)

Characters that resonate with readers

Every hero, every villain, every sub-character needs to create a bond with readers, give the reader something to root for, something to emote over, some joined experience to cause the reader to join the battle to conquer the enemy and reach the goal

Good characters make choices – sometimes those choices are good, and sometimes they’re not. Readers can cheer for the character making a poor choice or is a victim if the character is someone we have some respect for, is basically admirable in some way, has some kind of quirk or gift, doesn’t deserve the treatment received, needs or wants something all readers can relate to or at least understand, knows the depths of despair or fear, wants to be challenged and overcome those challenges.

Does Genre matter? – Not much.

Characters should be identifiable/bondable no matter where or when they exist and live out their story. Their setting helps define them, but they still have universal needs and a conflict to overcome.

The Character Arc

GOOD STORIES always contain these elements:

Someone has a need – Problem/Issue – the larger, more widely known need raises the stakes

Why the need can’t be met – Conflict

What must happen to obtain the need – what is the character desperate to do/sacrifice in order to achieve the goal – Motive

Denouement – Ending appropriate to genre

Give your character a specific goal, whether internal or external, a conscious need or one obvious to everyone but the character—a false goal or hidden agenda goal.

The arc is the story of how he or she or it gets from Point A to Point B.

Does he grow, maintain, backslide?

Good story shows some character evolution in either him or herself (growth-positive)

or the primary role is to influence others (maintain or stay nearly flat or static),

or devolve/fall

Character-driven vs. Plot-driven stories

In character-driven stories, the Character growth is more outstanding than what happens—the character is the story

Plot-driven would be some story like a thriller where the mc is important, but perhaps can be anyone

Building a character and resources

Where can I find inspiration for characters?

Combine several attributes of people in your circles, but be careful to always change names and combinations, never use any trait obvious or unique that identifies or is associated with a particular person.

Obituaries are awesome.

Sit at a park or at a local grocery or department store and people watch, but not in a creepy way.

Description

Characters should be able to be imagined or pictured for your reader, but not necessarily described so tightly that there’s no room for interpretation. Here’s where show don’t tell and word/phrase choice becomes important. You want readers to bond, and the way you do that is get them involved or able to identify with your characters.

Physical Attributes

Using Body Language –http://changingminds.org/techniques/body/body_language.htm -A great resource on how emotions and mental states reveal themselves in body language.

http://www.faceturn.com/ – to view facial expressions on a digitally-generated face

For ideas on dress/costume, historical or cotemporary: www.CostumeGallery.com – provides information on clothing from the 18th Century to the 20th Century.

http://www.costumes.org/ – a broader resource on historical clothing.

Names

Names can also be a plot device to set the tone and pace of the story, as well as create an obvious picture of the character’s personality traits or supposed traits; ethnic names, nonsensical names, family names, gender neutral or gender specific – these can create a particular picture in the reader’s mind as much as eye color and manner of speech

One place to look up names in any era, learn the most popular names of historical periods, cultures, or develop a unique name of your own: http://www.names.mongabay.com/baby_names/

Background

Here’s where many writers get into trouble.

Well-rounded believable characters should come from somewhere – you the author need to know the backstory – the why he or she got to be the way he or she is; but the reader doesn’t need every detail. Characters should encompass some but not necessarily all of the following.

Need some manner of speech, some personality trait, some unique (even if it’s ordinary or anonymous) description, some quirk, some sense of style, likes and dislike or preferences.

They need some sense of morality, some strengths/gumption, and weaknesses/flaws, some gifts, talents, connections—whether friends or work or family, some grounding—unless that’s part of the story, like Robert Ludlum’s Jason Bourne.

Personality

Your character has to be the only person who can overcome the particular problem laid out in the story – what gives him or her the ability to do this? What makes him or her the only or best one to solve or meet the conflict that leads to the resolution.

Find your character’s personality type, or get some ideas for creating more depth here http://www.humanmetrics.com/cgi-win/jtypes2.asp

Myers Briggs personality types – myersbriggs.org

Internal/External motives and characteristics

Is your character aware of what he or she truly needs or wants? What does she believe about himself vs. how others perceive her? What does he think he needs in order to be happy, to deal with a problem in his past. What makes him controlling or a doormat?

Fictional Character Development Tools

Worksheets for character and setting may be downloaded from www.lisalickel.com

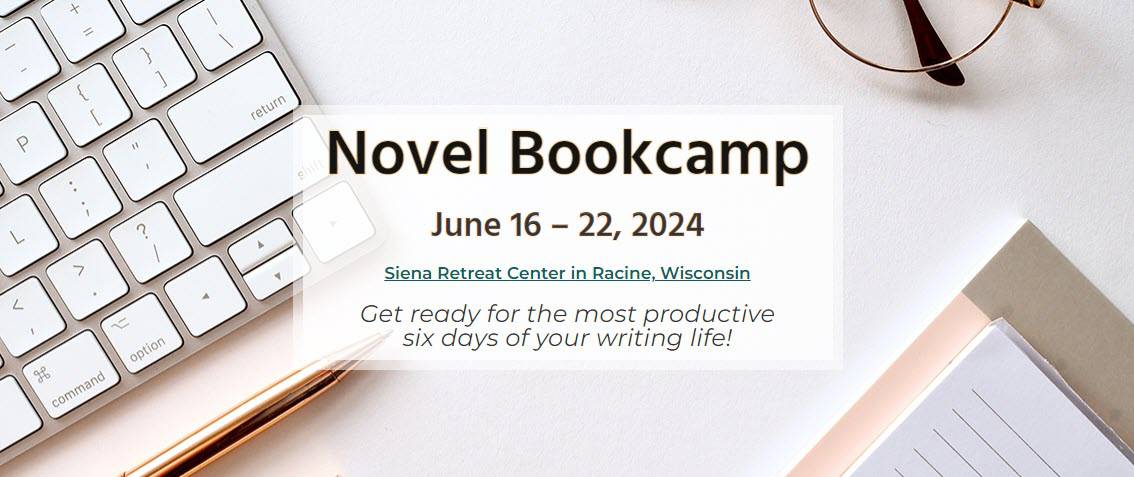

And best of all, we’ll work with you at Novel Bookcamp in June!